Historic Archive - Catalogues

Catalogues

The Baker Foundry, Newport, South Wales

Compared with other foundries featured on the Lost Art site, the Baker Foundry is considerably less celebrated. Situated in Newport, Monmouthshire, it was a long distance from the Scottish heartlands of most of the major names in decorative cast ironwork. However, Welsh foundries were responsible for producing both elaborate and decorative ironwork as well as the more everyday items that provided the bulk of the employment for iron workers. Like many of the major competitors, the company also maintained offices in London, from where the catalogues etc were issued.

Founded in 1880 as W. A. Bakers Foundry, the company operated out of its Westgate Works, although the company was also linked to an ironmongery shop in the city that sold many of its products, apparently stocking everything from bedsteads to ammunition.

The company also supplied structural and decorative ironwork to local civic developments, with over 100 tons of their products being used in the building of the Newport 'Town Bridge', including parapets as well as cast light fittings.

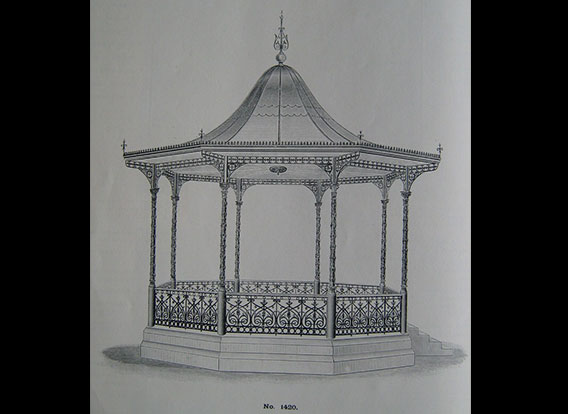

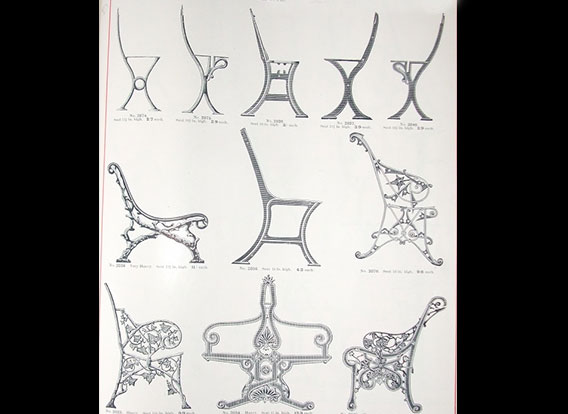

A quick look at the Baker catalogue will show that it produced many items in common with other foundries of the time.

Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss, Wolverhampton

In contrast to the majority of the companies featured in the Lost Art Archive, the Wolverhampton based company of Bayliss, Jones and Bayliss were focussed more on the design and production of gates and railings rather than that of decorative castings. As a consequence, much of their work was focussed on the production of ‘wrought’ (or ‘worked’) iron rather than the casting of shapes form molten metal in moulds.

The company was established in 1826, growing to become a large employer and significant presence within the industrial landscape of its home city, although it also maintained offices and representation in London, as did the majority of the significant foundries.

The gates and fences produced by BJB ranged from the ornate to the functional and although styles evolved, the core of their production range and methods remained relatively constant for a period of 75 years covering both the Victorian and Edwardian periods, finally suffering a decline during the period of austerity beginning with the Second World War. By this time, BJB had been absorbed into the giant G.K.N. company where it remained as a semi-independent operation until the 1970’s when the parent company finally collapsed. By this time BJB had shifted focus onto more industrially focussed products such as railway fixings and transmission wires for electrical distribution.

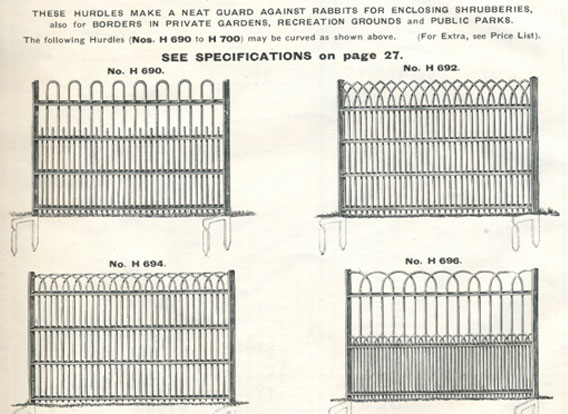

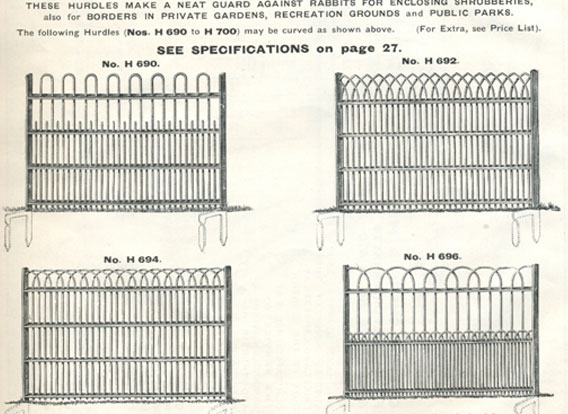

Given the classic nature of the Bayliss products, Lost Art Limited reproduce a number of designs that are either replicas or close approximations of their styles. Included in this is the ‘game proof fencing’ which can be produced in a number of styles and sizes.

The estate style fencing illustrated in the BJB catalogue is available from Lost Art Limited. A classic design and a common feature of British countryside estates, this type of fencing was installed by the mile throughout the country. Lost Art Limited offer a variety of variations on the classic design and also include gates, either to standard or bespoke sizes and designs. Similarly, the hoop top design of fencing, much used in public parks, is also produced by Lost Art Limited for either supply or for supply and installation, as is the case with all of our products.

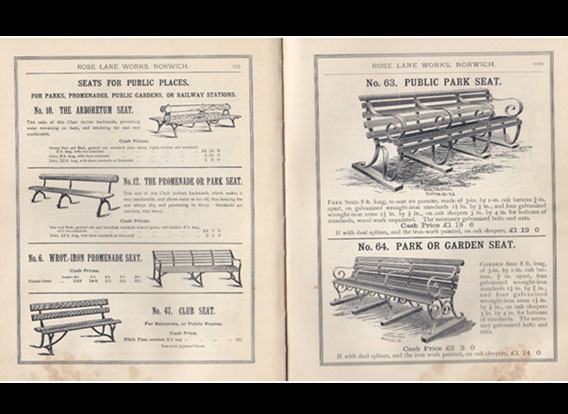

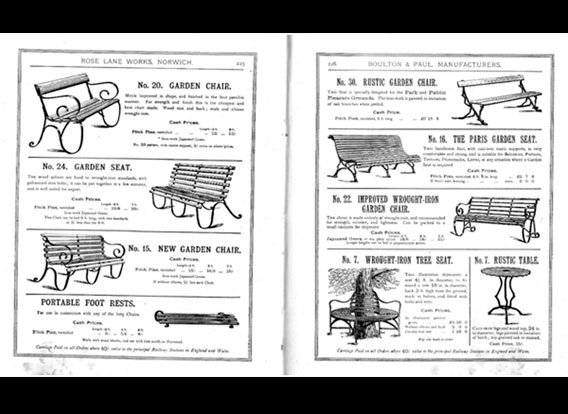

Boulton and Paul, Norwich

A Norwich based company, dating back to 1797 when records show that they had an ironmonger’s shop on Cockey Lane in the city, which was retained until 1869, despite having moved production to the Rose Lane Foundry several years earlier.

Like the Wolverhampton firm of Bayliss, Jones and Bayliss, the main focus of the Boulton and Paul output was the production of gates, fencing and metal structures such as farm buildings and shepherd’s huts, constructed in corrugated iron – an example of which can be viewed at the Chiltern Open Air Museum, although this is a mission hall building rather than a farm structure.

In terms of decorative works, the firm are best appreciated for the involvement of the influential designer Thomas Jeckyll, whose style was both novel and influential then and increasingly collectible now. Whilst he designed gates for the company, he was also responsible for interior fittings such as fireplaces. His combination of influences and interest in natural forms places him alongside such celebrated figures as William Morris and Christopher Dresser.

A reproduction of a Jeckyl design was chosen for inclusion as a ceiling rose for the bandstand designed and produced by Lost Art Limited for Beaumont Park in Huddersfield - our carving for the casting process is illustrated alongside.

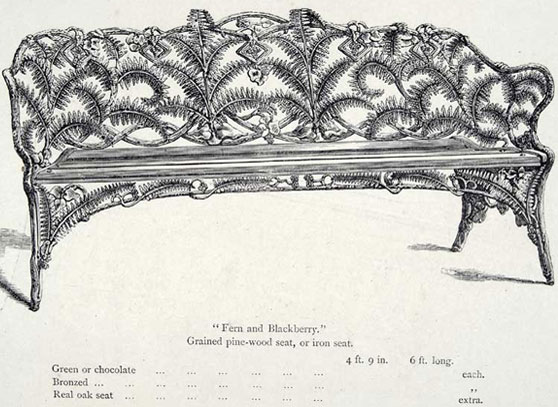

The Lost Art Limited archive includes an original copy of a Boulton and Paul catalogue. Although the company did produce some benches, as their focus was more on wrought rather than cast iron, compared with their mainly Scottish contemporaries, their range of seating included a greater number of wrought iron based benches rather than those featuring decorative cast iron ends.

Lost Art Limited do produce a number of benches that are similar in style to both the wrought and cast iron benches offered by Bolton and Paul.

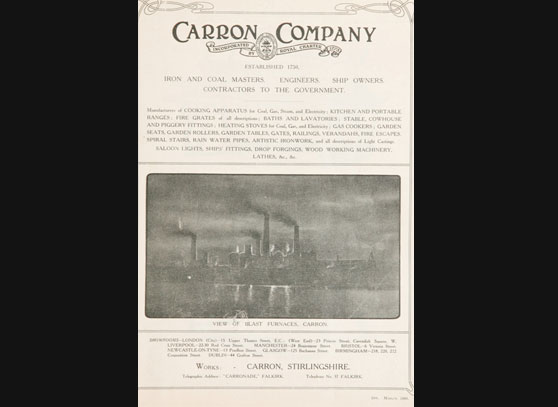

Much of the early work of the company was for munitions for the Royal Navy, although they did also produce parts for the early steam engines produced by James Watt. However, there were considerable problems with the quality of the work, resulting in the loss of the navy contracts - with all Carron Company cannons being removed from all Navy ships. At around the same time the company were also the subject of a less than complimentary poem by Robert Burns who had been denied entry to the works.

The response of the company was to improve the design and finish of their product and the success of their 'Carronade' cannon - also known in the Navy as 'The Smasher' helped make the the company a success, so that by the second decade of the 19th Century, the Carron Company operated the largest ironworks in Europe. The company was that big that it had its own canal running the length of the works. This is also referred to in the biography of the company, which points to the scale of production in the descriptive title, 'Where Iron Runs Like Water'.

Although the Carron Company operated on a huge scale, a look through their catalogues will show that decorative goods made up only a very small part of their output and so, despite the scale of their production, the company is less celebrated for either its products or design influence than both the Coalbrookdale or MacFarlane companies.

The company continued production throughout the early Twentieth Century and contributed significantly to munitions production in both World Wars. As the company gradually shrank they did contribute to the overall appearance of the nation by producing pillar boxes and telephone boxes but this work was not enough. Despite diversifying into other materials the company finally closed in 1982.

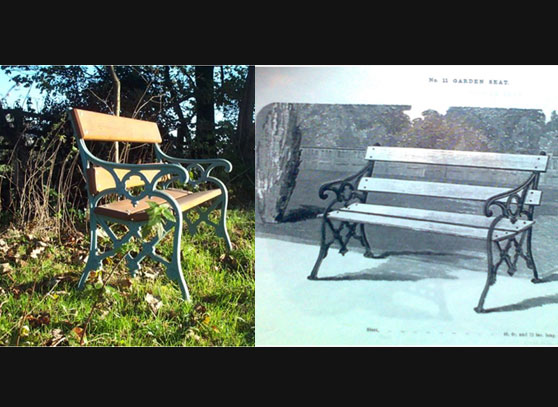

The Carron No. 11

The Carron No. 14

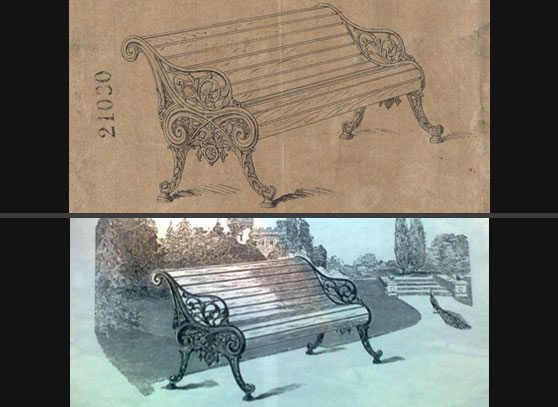

Refered to by Lost Art as the "Mystery Bench", following research by Lost Art we discovered that the more correct title was the Carron pattern no. 14 garden bench. The images above show an original registration document for the design and a catalogue illustration – we presume the peacock was an optional extra.

The Carron No. 14

The image above shows a reproduction bench to the original design. The length of the bench can be extended with the inclusion of an additional central support.

The Carron No. 4

The ‘Thorneythwaite’ Bench, referred to by Carron as pattern no. 4, the images show a reproduction plus the original registration document and a catalogue illustration.

The Carron No. 3

The Serpent design, shown in the Carron Company catalogue, and as produced by Lost Art Limited. As an illustration of the vagaries of Victorian copyright laws, a very similar pattern of bench also appears in the catalogue of the influential German von Rolf Foundry.

The Carron Company, Falkirk

Founded as a partnership between three men, the Carron Company was established in 1759 near Falkirk, Scotland, on the banks of the River Carron. The founders deciding to use the method developed at the famous and pioneering Coalbrookdale works which was based on using coke as fuel rather than charcoal. This process was helped by the local availability of coal and this use of newer processes is thought to have pushed less technologically advanced local ironworks out of business.

In addition to possessing (and producing) a number of examples of Carron Company benches, including designs no.11, 14, the latter being referredto as The Carron Mystery Bench, No. 4, which we refer to as the Thorneythwaite,and Lost Art Limited do have copies of Carron Company catalogues and promotional material as well as copies of original registration documents. However, as mentioned earlier, their production of decorative ironwork was limited and of generally less importance to Lost Art Limited activities.

The process of using coke as fuel was further refined as the foundry expanded, enabling the company to expand and to make further impacts on hsitory.

They became an early supplier of steam engine cylinders and also the first cast iron rails for the emerging railways. In 1778, the foundry, undertook the work that would ensure a lasting legacy to the world, building the first cast-iron bridge, Iron Bridge, taking two years to complete and still standing today. The foundry had to be further extended in order to cast the bridge.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, with the spread of wealth within society to include the middle classes, Coalbrookdale developed a wide range of decorative goods, including garden furniture, with the foundry producing vast numbers of benches, chairs, fountains and other goods, such as gates and railings. Many of the original works still exist today and Lost Art Limited have a history of both repairing originals as well as producing high quality reproductions that are to all intents and purposes identical to the 19th century versions

The works produced by Coalbrookdale are also a reflection of the use of high quality design, including the work of the most famous of these, Christopher Dresser, whose designs were not only beautiful but also both influential and revolutionary. He has been described as the first designer of the modern production age and incorporated natural elements into manufacturing design, succesfully bridging the gap between art and industry.

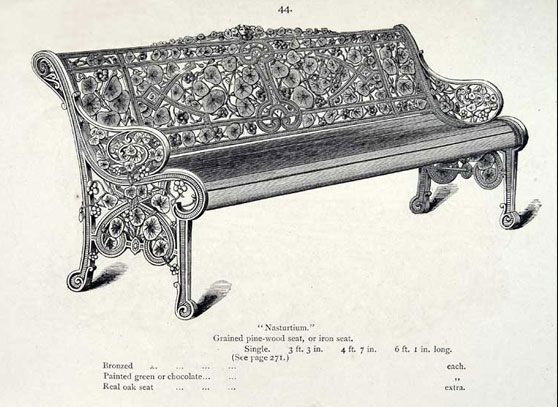

The image shows a Nasturtium bench as illustrated in an original Coalbrookdale catalogue.

The image above shows a reproduction Nasturtium bench produced by Lost Arts and currently residing in a tranquil corner of the garden of a stately home. The bench is available from Lost Art in the same lengths originally offered by Coalbrookdale and we also offer the option of a timber back rather than the cast iron panel.

The popularity of Coalbrookdale designs and the weakness of the copyright laws of the time (lasting only for 3 years) meant that many of their designs were soon copied by other foundries and care should be taken in selecting original benches.

Such was the reputation of Coalbrookdale that, following the Great Exhibition in London where the foundry were awarded a council medal in recognition of the remarkable originality of their work, the company were commissioned to construct the gates to Hyde Park in London.

As with many others of the great decorative foundries, the Coalbrookdale fortunes were greatly affected by the World Wars. For Coalbrookdale the situation was further complicated by the fact that the owning family, The Darbys were also Quakers and so until 1917 they would not involve themselves in the manufacture of weapons and munitions.

Following the Wars the foundry, like many others, found the economic conditions very difficult and a series of mergers and takeovers followed which ultimately has seen what remains of the Coalbrookdale Company continues to exist as part of the AGA heating and cooking range manufacturers.

The Lost Art Archive

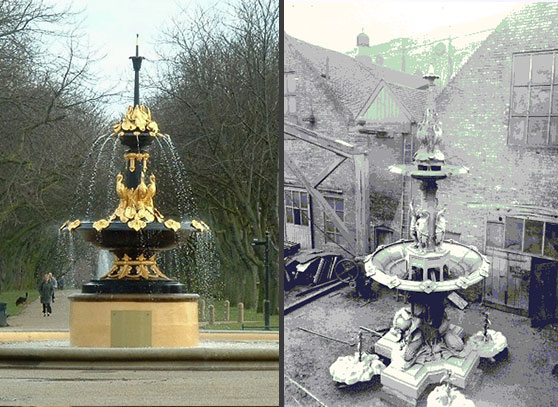

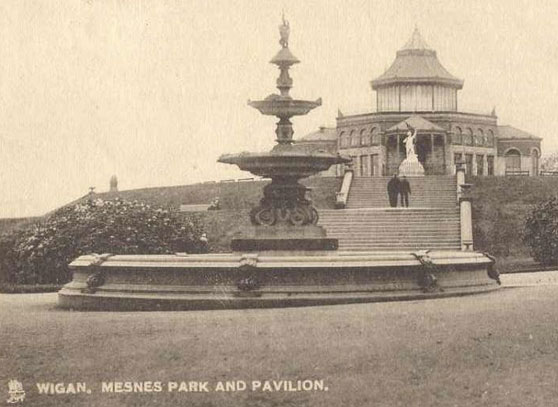

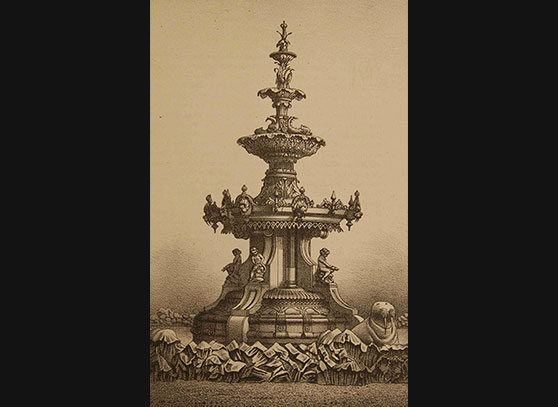

Having worked on projects involving a numebr of Coalbrookdale fountains, Lost Art Limited now have full sets of patterns to allow for the recreation of existing fountains or to engage in the Victorian practive of creating a unique fountain by combining elements of already exisiting examples.

The fountain shown in the previous image had been removed from its location in Wigan as long ago as the 1930's. Lost Art Limited provided and installed an exact copy of the original fountain.

In addition, Lost Art maintain an ever increasing library of original Coalbrookdale benches and castings which we are able to reproduce to the highest degree of accuracy and specification.

We also have access to a selection of Coalbrookdale archive material including original catalogues of both benches and other items.

Coalbrookdale, Shropshire

Perhaps the most famous and certainly one of the most influential of all the foundries producing decorative cast iron goods, Coalbrookdale has a long and distinctive history, including considerable innovation within the manufacturing processes, as well as true excellence in design.

The Coalbrookdale Foundry was initially established by Abraham Darby of Shropshire in 1709 and run by successive members of the Darby family through most of the 18th Century. The area had previously hosted an earlier foundry but the furnace had exploded and then allowed to become derilict.

Darby rebuilt the Coalbrookdale Furnace, using coke as the fuel and this enabled him to produce simple cast iron goods such as pots and pans more cheaply than his competitors, allowing him to prosper.

The Sun Foundry produced designs for gates, railings and bandstands but, as mentioned above, their speciality was ornamental fountains. A spectacular example of a Sun Foundry fountain can be seen in Fountain Gardens, Paisley. It stands 30ft high with a 12 foot bowl and is decorated with life size cast iron walruses. The fountain was a present to the town of Paisley by the Victorian philanthropist Thomas Coats and was described at the opening as 'an exceptional example of ornamental cast-iron manufacture and unlike any other example produced before or since'.

Despite producing such notable products the firm did not survive as its rivals did and moved out of Glasgow before the end of the 19th century, apparently relocating to Alloa but records are vague and the exact timing of their demise is unknown.

Designs produced by the Sun Foundry also found their way around the world, with their Squirrel Bench being found, not only in the Botanical Gardens in Glasgow, but also in the Smithsonian Institute in the USA, with the famous American Mott Company having adopted the design. Lost Art Limited also have a pattern for the production of this bench, having produced over 60 copies for the restoration of South Marine Park in South Shields.

A Sun design cast iron cresting was also supplied as part of the work undertaken by Lost Art Limited for the Southend-on-Sea Cliff Lift.

The Lost Art Sun Foundry Archive

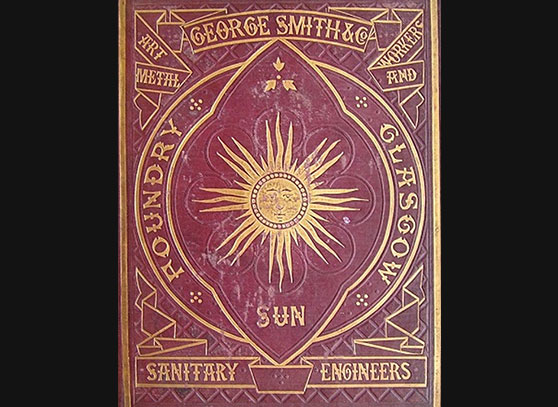

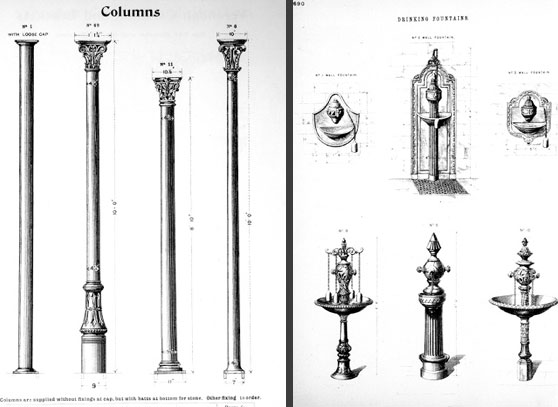

Lost Art have a number of copies of Sun Foundry catalogues, illustrating a wide variety of products produced by George Smith & Co. A couple of examples are shown below.

The Sun Foundry, Glasgow

The Sun Foundry name refers to the works base of George Smith & Co, a Glasgow based firm started in 1858 and who were at one time comparable in size to the more famous Saracen Works of Walter MacFarlane. Indeed, there are those who believe that the work of the Sun Foundry surpasses in decorative quality that of both the Saracen and Lion works, this being particularly true in the area of fountains, a product for which Smith's company were renowned.

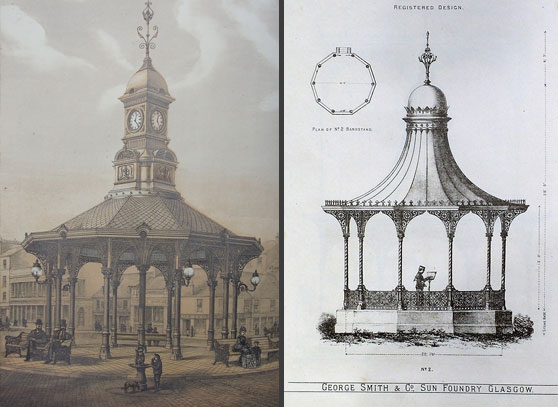

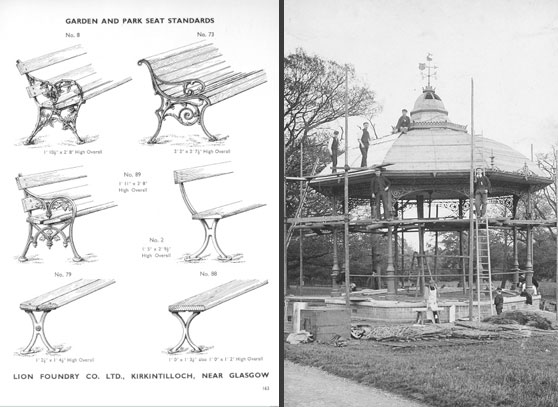

The Lion Foundry was based in Kirkintilloch on the outskirts of Glasgow. and was noted for producing attractive catalogues as seen in this example from the Lost Art Archive.

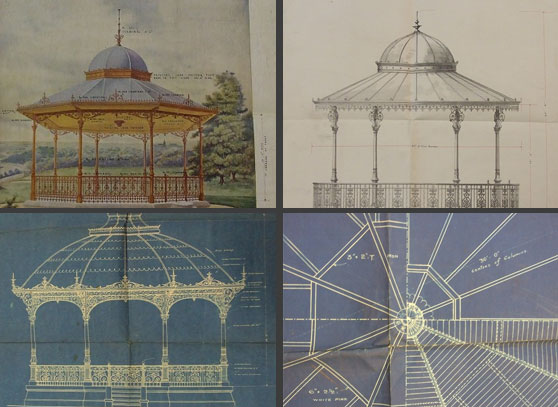

As the company developed there was a move from producing decorative components, including benches, to full scale structures such as bandstands and shelters.

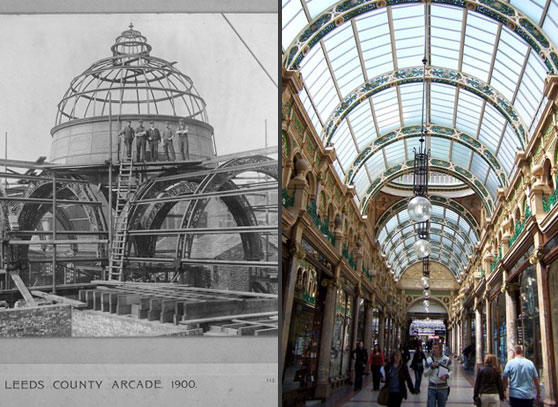

Lion Foundry’s first large project of note was supplying cast and wrought ironwork for the the County Arcade in Leeds, between the years of 1898 and 1900.

The company developing a particular reputation for work on theatre projects and worked with the celebrated designer Frank Matcham on projects such as the London Hippodrome. Matcham and two of his associates were responsible for work on the majority of theatres built in the boom years of 1890 to 1915, using the properties of cast iron to develop structures in a way that had not been possible previously.

The facade at the Grand Theatre, Blackpool is a Thatcham design and when they required a cast iron kiosk for publicity posters to be placed outside, Lost Art were awarded the project of producing the structure in a sympathetic Art Nouveau influenced style.

As the work for cast iron sturctures declined as the 20th Century progressed, Lion moved into the production of more prosaic components and structures, particularly bus shelters and fire escapes. Like the Carron Company they produced telephone boxes for the GPO and latterly pillar boxes for Telecom.

Although the company was involved in the restoration of cast iron elements of the Houses of Parliament, this type of specialised work was a rarity rather than a regular source of income and the company finally closed in the 1980s.

The Lost Art Archive

In addition to Lion Foundry catalogues, Lost Art also have a variety of other historical records from the Victorian Period.

These include copies of original illustrations supplied to potential clients.

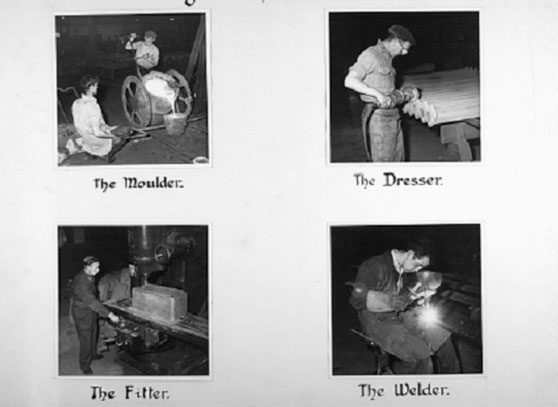

Lost Art also possess the skills shown in the Lion Foundry Catalogue which will allow us to restore or reproduce Lion Foundry bandstands and structures for any project. It should be noted that our Health & Safety considerations are greater than those shown here and in the image showing the construction of the bandstand!

The Lion Foundry, Kirkintilloch

Founded in 1880 by three former employees of the MacFarlane, Saracen Foundry, the Lion Foundry developed into a direct competitor to their previous employer through until the 1950s. In addition to the founders, the company also took the services of William Cassels, a designer and draughtsman from the Saracen Works. This may account for the similarity of designs of the two companies until Lion started to develop a more distinctive Art Nouveau style of designs when Cassells was replaced by James Leitch, who in turn was followed by his son of the same name.

Like their contempories, the Lion Foundry, McDowall Steven produced some distinctive decorative ironwork, including particularly notable fountains featuring idiosynchratic embellishments such as otters, fish and an octopus. However, consideration of their catalogues will confirm that their whimsical elements were solidly underpinned by the more usual products of foundries, with 450 designs of gutter being listed, although some of these were highly decorative in themselves.

The company were also renowned for both the quality and detail of their castings, with a good example being the façade of Central Station, Glasgow.

McDowall Steven & Co also produced a number of styles of bandstand. These were of particular note in that the Milton Ironworks examples made use of a different method of roof construction than the majority of their compeittors, such as the Saracen Foundry of the MacFarlane Company. Several of the McDowall Steven bandstands are still in existence, including an excellent example in North Lodge Park, Darlington, restored by Lost Art Limited and featured in Paul Rabbitts' definitive book on British bandstands.

McDowell Steven & Co Bandstands

The company relocated the foundry to Falkirk in 1912 but appear to have ceased trading sometime around 1920.

As a result of carrying out the restoration work shown above, Lost Art Limited carry examples of castings for McDowall Steven bandstands as well as patterns for further casting of these items. In addtion we also have copies of catalogues which include detailed illustrations of many of their products.

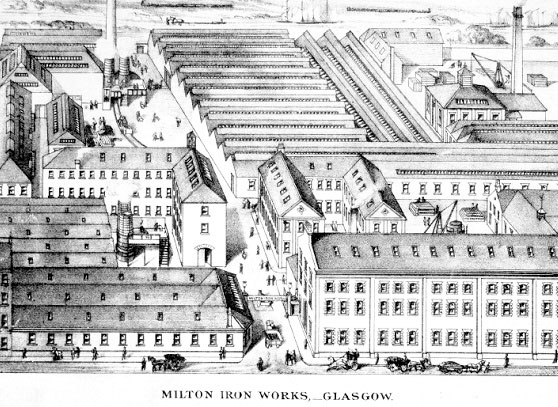

The MacDowall Stevenson Company, Glasgow

The origins of the McDowall Steven company can be traced back through one of the founders, James Edlington, to the earliest days of the great Glasgow foundries. As with many other of the iron companies, the firm McDowall Steven & Co was the eventual outcome of a number of mergers and takeovers, the final company emerging in 1862, with the foundry named as the Milton Ironworks.

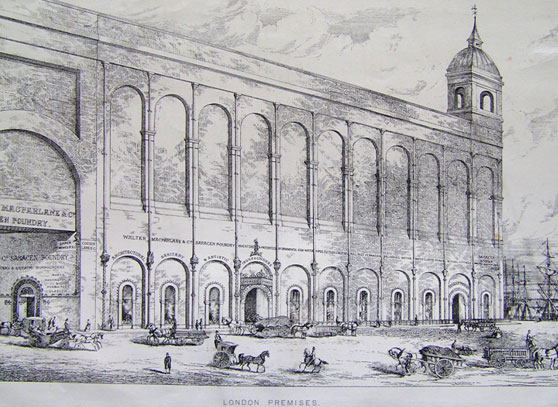

As with many of the Scottish foundries, the company also had a London office and warehouse. Theirs was similar in size to many of the large distribution centres that can now be seen alongside our motorways, but considerably more stylish.

Whilst Walter MacFarlane led the initial success of the company, its worldwide reputation for decorative work can to a large extent be ascribed to his nephew and successor, also known as Walter MacFarlane.

The younger Walter initiated a process of standardising designs for decorative ironwork products such as railings, fountains, bandstands and architectural features, components of which could also be moved amongst different products to create apparently different designs. He also made use of the greatest architects of the day in order to provide distinctive and high quality designs. One architect, James Boucher, was commissioned to design a stunning showcase building for the products at the Possilpark site, including a glass and iron dome and elaborate Gothic gateway.

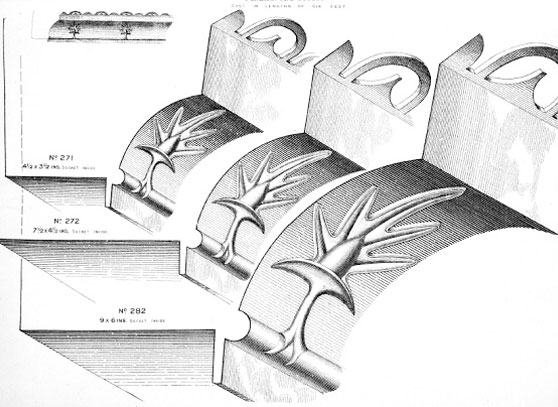

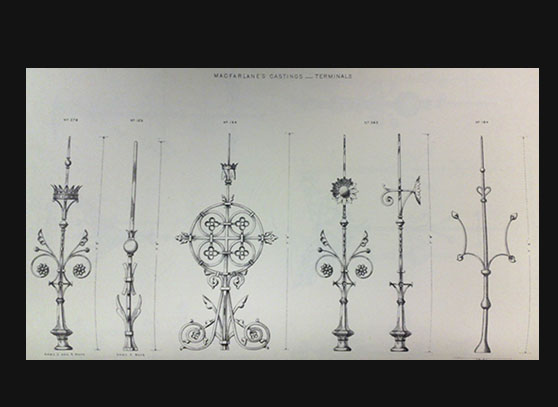

The above image show a page from a volume of the MacFarlane catalogue featuring different designs of roof terminals. The client could then choose which was to be included in a particular design, for example, on a bandstand.

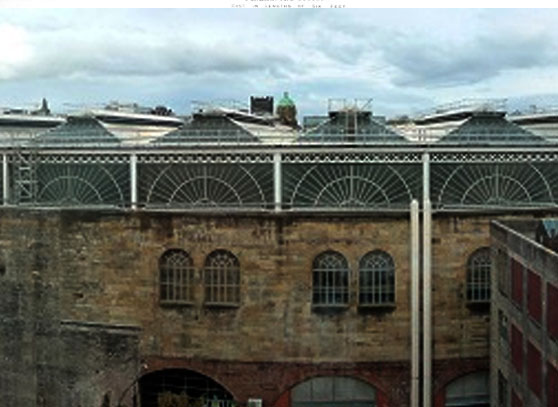

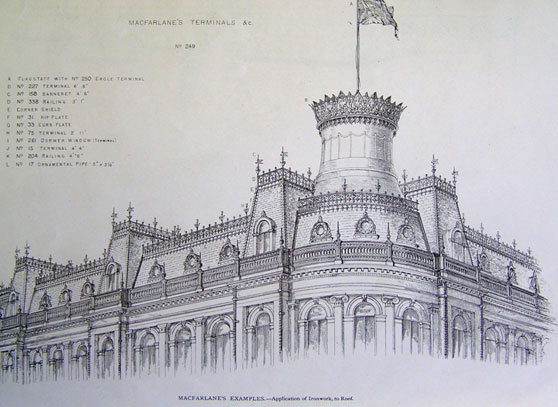

The above image is an illustration from a MacFarlane brochure which illustrates a building featuring different components, which are identified by their catalogue reference number.

As production of the decorative ironwork boomed, and a quick consideration of their huge 2 volume catalogues will bear testament to the range of items, their products were shipped, not just around Britain but throughout what was then the British Empire and beyond. Some of their most famous products still bear testament to their design skill and production values, such as the huge iron and glass Kibble Palace, (originally designed as a conservatory for an imposing house, became and still is home to Glasgow Botanical Gardens). Many of their fountains and bandstands are still found around the UK, although many fell to the desire for scrap metal during the Second World War.

An illustration of the top section of a magnificent MacFarlane drinking fountain, followed by a photograph from inside a Lost Art restoration of the same style of fountain, demonstrating the complexity and detail of the decorative ironwork.

Not only did WWII see the removal of many Macfarlane products from public areas but indirectly hastened the decline of the company. Required to produce munitions for the war effort, the years of austerity that followed removed much of the need for decorative ironwork. Whilst the company did produce a considerable amount of plumbing piping for the post-war housing boom, there was a steady decline, especially following the introduction of plastic guttering and plumbing and although like the Carron Foundry, they also produced red telephone boxes the foundry was finally closed and demolished in 1967.

The records, literature and patterns of the company appear to have gone with the building and so where restoration is required this can often involve recreating patterns based on catalogue illustrations and other historical documents that have survived, such as those in the Lost Art Archive.

Lost Art Limited have extensive experience of repairing, restoring and recreating Macfarlane designs.

The bandstand at South Marine Park had been completely removed but was recreated from drawings, illustrations and catalogues held in the archive, which enabled us to produce patterns for each of the required components.

The MacFarlane Pattern 224 bandstand was a particularly popular design, installed in parks throughout the country. The following images show an example that was completely recreated and installed in Wandle Park, Croydon by Lost Art, followed by a the same model of bandstand in Victoria Park, St Helens, which was rescued from a semi-derelict state by Lost Art.

As mentioned earlier, it can be seen that, despite being similar in basic design, the bandstand featured in the illustration above, taken from an original catalogue and the following image showing a bandstand based on that design but featuring some different details.

The image shows a MacFarlane bandstand, produced and installed by Lost Art in Wandle Park, Croydon. Also including the image are some of our Cartmel benches and variation on our gameproof fencing.

Our library contains a significant number of items relating to the MacFarlane company. These range from original copies of different volumes of the foundry catalogue and also includes copies of blueprints, working drawings and promotional illustrations, with the latter serving to illustrate proposed colour schemes. This is a useful research tool when trying to recreate bandstands dating from a period before colour photography.

In addition, we now have a large selection of patterns enabling us to cast replica components for Macfarlane products, either to replace missing or damaged parts of an existing structure, or to fully recreate a missing park feature, such as a bandstand or a selection of seating.

Walter MacFarlane and Company, Glasgow

The Glasgow based, Saracen Foundry of Walter MacFarlane and Company was one of the most successful and influential of the Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries and has left a legacy of decorative ironwork, which is at least the match of any of its city rivals.

Founded by Walter MacFarlane, the company evolved from an earlier partnership from around 1850, which took over a disused brass foundry in Saracen Lane – the location giving the name to the foundries that followed. Walter himself had been a trainee jeweller, followed by a blacksmithing apprenticeship, which in turn led to his becoming moulding shop manager at a local foundry before setting up in business himself.

The early business focussed on the production of sanitary goods, with the success of the firm built on the more ordinary latrines and urinals than the decorative work for which they are now famed.

In 1872 the foundry relocated to what became known as Possilpark and, as the fortunes of the foundry boomed, so did the population of the area, rising from 10 to 10,000 in just 20 years. Along with the rise in the fortunes of the foundry and the population of the area, such large industry also created problems of pollution and Walter was known in some quarters and not too affectionately as “the Laird of Fossiltoun.”

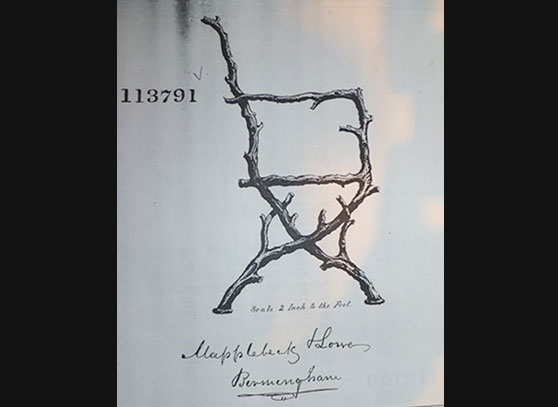

Mapplebeck and Lowe

Based in Birmingham and Sheffield, the company advertised themselves as both silversmiths and foundry ironmongers. They offered an eclectic range of goods, from a patented snuffer to the ‘Automaton Roasting Jack’ an addition to the cooking range to allow for the preparation of whole animals.

The Lost Art Archive reveals that they also produced some garden items as demonstrated by their registration for the design of a bench end in a rustic style.

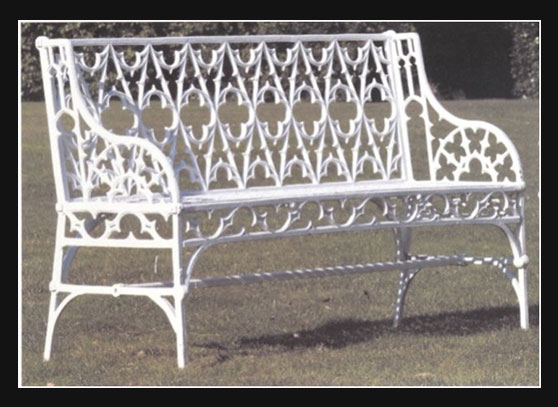

Barnard, Bishop & Barnard

Based in Norwich, the company was originally formed in 1844 as a supplier of agricultural products. As the company grew, their product range expanded, with a notable project being the supply of a prefabricated cast iron and timber lighthouse, supplied to the Govermment of Brazil.

Decorative ironwork was part of their output, with some particularly notable gates being produced by the company as well as some fine garden furniture. Some of their finest designs were the work of the notable aesthetic designer Thomas Jeckyll, for instance, the “Four Seasons”gates,featuring swallows and doves and branches of trees flowering and bearing fruit. The Lost Art collection includes a fine example of a highly decorative cast iron bench produced from his design.

In terms of decorative works, the firm are best appreciated for the involvement of the influential designer Thomas Jeckyll, whose style was both novel and influential then and increasingly collectible now. Whilst he designed gates for the company, he was also responsible for interior fittings such as fireplaces. His combination of influences and interest in natural forms places him alongside such celebrated figures as William Morris and Christopher Dresser.

A reproduction of a Jeckyl design was chosen for inclusion as a ceiling rose for the bandstand designed and produced by Lost Art Limited for Beaumont Park in Huddersfield - our carving for the casting process is illustrated alongside.

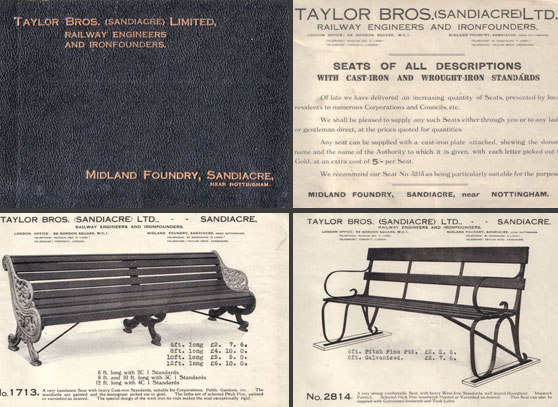

Taylor Brothers and other British foundries

The Lost Art archive contains documents and catalogues relating to a large number of these less celebrated foundries, including Boulton and Paul, Yates and Heywood, Illingworth and Ingham, and Archibold Kenrick, as well as examples of their work in our collection, all of which are available for production. For example, the catalogue produced by the Taylor Brothers of Sandiacre (see image) 1reveals them as focussing largely on production for the railway industry. However, they also supplied numerous styles of seating in both cast and wrought iron. As was the state of the copyright laws in that period, many of the designs will also be familiar as being available from their competitors. Incongruously, the last page of their seating catalogue offers a garden roller to customers. It should be noted that the prices quoted have changed somewhat in the intervening years.

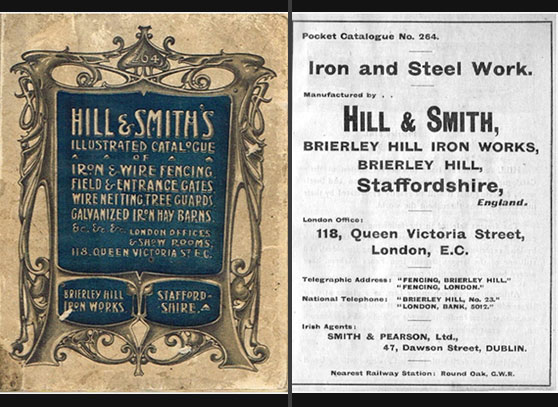

Metal Working Companies

Other ironworks focussed less on the casting of iron from patterns and more on the production of fencing and associated products such as gates and tree guards. In addition to the Bayliss Company, there are many other examples, such as Hill & Smith. Based in the Midlands. Lost Art retain a copy of one of their catalogues in the archive and can reproduce any items as required or base new designs on their originals, should a project require this.

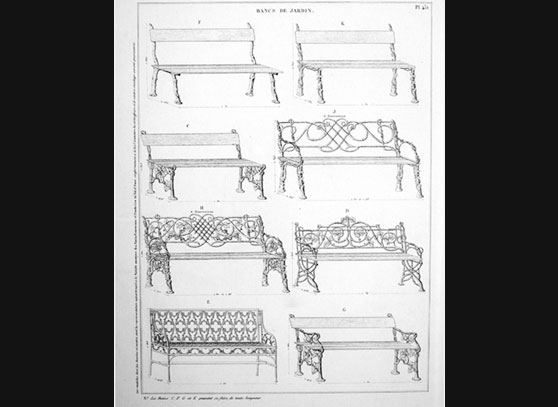

Overseas Foundries

Although the UK and Scotland in particular were the world leaders in both industrial and decorative ironwork during the mid to late Victorian period, there were many thousands of foundries across the globe, including some notable producers.

As mentioned earlier, the copyright laws of the time were considerably less defined that is the case today and the same or very similar designs can be found in the catalogues, not only in the same country but literally around the world.

Overseas Foundries

The Serpent bench, offered by Lost Art Limited is often attributed to the influential German von Rolf Foundry but several foundries in the UK alone produced a very similar and largely indistinguishable form of the same bench.

The Val D’osne Foundry

Perhaps the most significant French producer of decorative ironwork, with a vast range, including fountains, statuary and architectural castings.

The Val D’osne Foundry

In a similar vein to the misattribution of the Serpent design, one of their most frequently found bench designs is often attributed to the Val D’Osne Foundry but was in fact originally produced at the Yates and Heywood Foundry in Rotherham.

American Foundries

Two American foundries are particularly noteworthy.

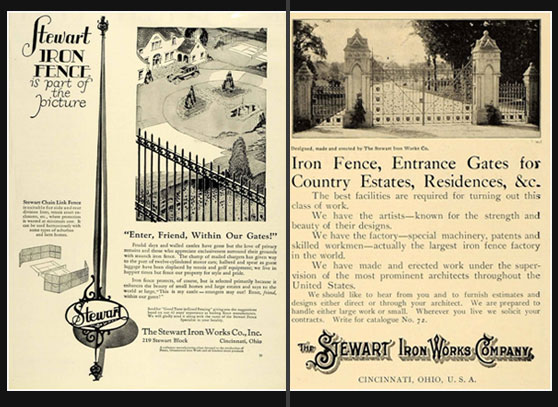

The Stewart Company of Cincinnati, Ohio were particularly noteworthy for their gates and fencing.

The Mott Ironworks

Based in New York, The Mott Company was one of the major producers of both architectural ironworks in the USA. However, many of their designs were close to, if not exact replicas of earlier designs from UK companies.

Mott produced significant numbers of fountains, many of which are very similar to those of several Scottish Foundries, particularly the Sun Foundry of Glasgow, with whom Mott had considerable links.

The Squirrel Bench, originally a Sun Foundry Design was also produced by Mott, with a surviving example not to be found in the gardens of the prestigious Smithsonian Institute.

Lost Art now also have a pattern for the production of The Squirrel Settee (as it was originally known) and have supplied these to various restoration projects and private buyers around the UK.

The Mott Company buildings were eventually destroyed by fire and little of their records remain, however, Lost Art do have access to some of these within our archive.

Other notable UK and overseas companies

A quick round-up of the history of architectural and decorative cast iron will reveal that a few major foundries dominate accounts of the period. Many of these are covered as part of this website. However, it should be remembered that there were many hundreds of foundries around the UK, many of whom were producing rather mundane, everyday goods but occasionally would make a small foray into the productions of more decorative items.